As you might have seen from my earlier posts on this blog, my background is in languages, and I have a Masters in Literary Translation. It’s International Translation Day today, so I thought I’d share the love for something I’m hugely passionate about.

I fully believe that the world would grind to a halt without translation. In my eyes, it is practically irresponsible to deny others the opportunity to learn from and communicate with other cultures. Without literary translation, for example, we would not know about Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince (now of course a classic). Neither would J.K.Rowling’s Harry Potter have had such global success had it not been translated into more than 75 languages so that others could enjoy it too.

I got into translation through studying French at school. I absolutely relished the opportunity to play with the language, and see the ways in which its structure and word use differed from English. I chose to take that study further, and did a BA in French and Spanish at the University of Hull, then the MA in Literary Translation at the University of East Anglia.

What makes “literary” translation different?

First off, I’d like to set one thing straight: while both professions l i t e r a l l y translate from one language into another, a translator does it through writing whereas an interpreter uses speech – they’re the ones you see in interviews. Professionals nearly always translate from another language into their own.

Sorry, that always gets me …

Anyway.

In the most basic terms, literary translation is all about the literature. Rather than translating, say, legal documents or tourist guides, literary translation focuses on books: poetry, prose, plays, religious texts, memoirs … The more creative stuff. It’s not just about changing words; you need to maintain tone and atmosphere when translating literary and non-literary texts. It’s a bit like analysing literary literature and creative writing rolled into one, which is right up my street!

What do you like about literary translation?

In the summer holidays, I worked at a World Heritage Site, and volunteered to translate an information leaflet from English into French. It was, shall we say, Not Fun. The site had been given UNESCO status for its industrial heritage, and there was a lot of technical language involved! Nevertheless, I persisted with the challenge, and got it checked to be used by French tourists. It gave me valuable insight into the realities of professional translation, and definitely solidified my preference for literary translation!

I love that I’m bringing new stories to the market that might not otherwise have been read. I love playing with the language and discovering new metaphors and similes (for example, the French equivalent of “It’s raining cats and dogs” is “Il pleut des cordes” – “it’s raining ropes!”). I love reworking the sentences until they “work” in English; it’s not just about translating word-for-word when the sentence structure or phrasing is completely wrong in English!

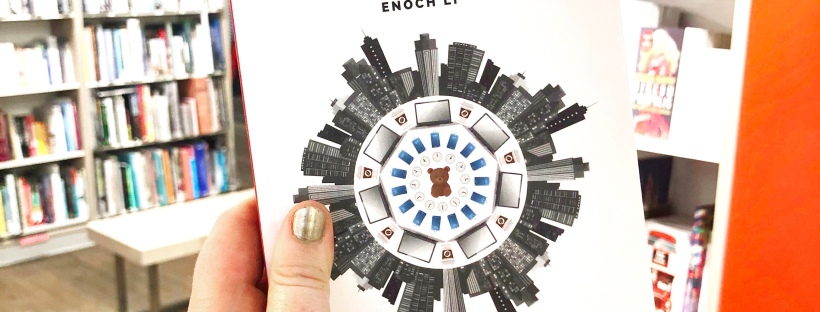

That’s actually what led me to editorial; for me, copy-editing is like popping bubblewrap! Indeed, I was able to use these skills when helping out on Enoch Li’s Stress in the City. For example, Enoch, for whom English is a second language, once used the phrase, “the ice does not stand at three feet only in one day’s cold”. While this could be tidied up into “you don’t get three feet of ice in one cold day”, we would actually say “Rome wasn’t built in a day”. Ultimately, though, we made an editorial decision to keep the original – it just worked better in that context. And that is what literary translation is all about!

What is the most challenging thing about literary translation?

As I said, you have to think about the tone, the atmosphere, the word choices – it’s not as straightforward as “bonjour” = “hello”. It could mean any number of things – and yes, while, there are a whole variety of words that could have been used – “coucou”, “salut” etc – to vary formality (“hi”, “hey”, “s’up”), it’s the wider context that determines it in English. Maybe you can’t quite make it work, so you have to add an adverb – “Hello”, xe said warily. It’s a challenge!

And not only that, but you have to be aware of the simple things on top of that!

And translator’s choice can be subjective. I’ll always rue getting marked down in my dissertation because I kept the name of a fantasy world the same – Sillyrie. I thought it sounded magical, fairy like, and kept that tone in English. My marker, however, felt that I should have translated it perfectly to “Sillyria” (Syrie = Syria, Russie = Russia etc).

Moving on …

What advice would you give to somebody thinking about training to be a literary translator?

- Be prepared for a lot of late nights asking friends and family to check your work because you’ve forgotten what your first language is and are typing in some sort of amalgamation of the two.

- It’s the little things – the nuances in language – andthe big things. Remember that.

- Network! It’s so good to have a group of people that you can bounce ideas off, or get help from.

- Join the Translator’s Association (part of the Society of Authors).

- Have fun with it!

The #NameTheTranslator movement is growing, as it should be. Without literary translation, we’d miss out on so many books – like Leila Slimani’s Lullaby, for example (translated by Sam Taylor), or Toshikazu Kawaguchi’s Before the Coffee Gets Cold (translated by Geoffrey Trousselot) – and yet the work put in by the translator is often overlooked. But that work is put in, and it can take quite a while!

So with that in mind, what are your favourite books in translation – and who do we have to thank for them?

Something to think about …